Published: January 13, 2026

From Chrome 144 you can use the new <geolocation> HTML element. This element

represents a major shift in how sites request user location data—moving away

from script-triggered permission prompts toward a declarative,

user-action-oriented experience. It reduces the boilerplate code required to

handle permission states and errors, and provides a stronger signal of user

intent, which helps avoid browser interventions (like quiet blocks).

This launch is the result of extensive real-world testing and rigorous discussion with the web standards community. To understand the utility of this element, it is important to examine the history of its development and the data that drove its design.

From generic <permission> to specific <geolocation>

The <geolocation> element is the latest evolution of the Page-Embedded

Permission Control initiative, where it initially was proposed as a generic

<permission> element with a type attribute (see the original

explainer). The value of

the type attribute (for example, "geolocation") would determine the type of

the requested permission. For example, the initial proposal includes values such

as camera, microphone, and geolocation.

Validation of the concept

We ran an origin trial for the generic <permission> element from Chrome 126 to 143.

The aim of this trial was to test the hypothesis that a dedicated,

in-context button would improve user trust and decision-making.

The results from this origin trial supported the validation of this core concept:

- Zoom reported a 46.9% decrease in camera or microphone capture errors (such as system-level blockers) by using the element to guide users through recovery.

- Immobiliare.it saw a 20% increase in successful geolocation flows.

- ZapImóveis observed a 54.4% success rate in users recovering from a "previously blocked" state when presented with the element.

Redefinition of the design

While the concept proved successful, the implementation required refinement. Feedback from browser vendors—including Apple (Safari/WebKit) and Mozilla (Firefox)—indicated that a "one-size-fits-all" element introduced significant complexity regarding unique capability behaviors.

Consequently, we transitioned from a generic permission control to targeted,

capability-specific elements (see WICG

discussion). The <geolocation>

element is the first of these specialized controls to launch. Following this,

we're also developing a dedicated <usermedia> element (for camera and

microphone access), which has its own separate origin

trial.

Unlike the original proposal, which focused on managing permission state (that is, allow or deny), these new elements function as data mediators, effectively replacing the need to call the JavaScript APIs directly for most use cases.

| Feature | Geolocation JS API | <permission> HTML Element |

<geolocation> HTML Element |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triggering Event for Permission Prompt | Imperative script execution (getCurrentPosition) |

User clicks on the browser-controlled <permission> element |

User clicks on the browser-controlled <geolocation> element |

| Browser Role | Decides prompt based on state | Acts as a permission mediator | Acts as a data mediator |

| Site Responsibility | Manually call the JavaScript API, handle callbacks & manage permission errors | Implement geolocation API once permission has been granted |

Listen to location event |

| Core Goal | Basic location access | Permission request | Permission request and location access |

Why use the <geolocation> element?

Currently, geolocation flows rely on the Geolocation API, which triggers permission prompts that can interrupt users if fired out of context or even on page load. Crucially, reliance on these imperative prompts is becoming less viable due to browser interventions. For example, Chrome actively blocks permission requests if a user has dismissed the prompt three times, enforcing a temporary quiet block that initially lasts for one week. This means legacy code attempting to trigger a prompt may silently fail, leaving the user with a broken experience and no clear way to enable the feature. Furthermore, standard prompts often lack context. If a prompt appears unexpectedly, users may block it reflexively or accidentally, unaware that this decision creates a permanent block that is difficult to reverse. This context gap—rather than the feature itself—is a primary driver of high denial rates.

The <geolocation> element resolves the context gap problem by ensuring

requests are strictly user-initiated. This model provides three distinct

advantages:

- Clear intent and timing: By clicking a use location button, the user explicitly signals their intent to use their location at that specific moment. This signals that they understand the value and actively want to use location, turning a potential block into a successful interaction.

- Simplified recovery: If a user previously blocked location access when browsing a site (perhaps by accident or lack of context), clicking the element triggers a specialized recovery flow. This helps them re-enable location at the moment when they actually want to use location, without the friction of navigating deep into the browser's site settings.

- Automatic refresh: If permission is already granted, clicking the element acts as a refresh button, fetching new data immediately without re-prompting.

Implementation

Integrating the element requires significantly less boilerplate than the

JavaScript API. Instead of managing callbacks and error states manually,

developers can add the tag to the page and listen for the onlocation event.

<geolocation

onlocation="handleLocation(event)"

autolocate

accuracymode="precise">

</geolocation>

function handleLocation(event) {

// Directly access the GeolocationPosition object on the element

if (event.target.position) {

const { latitude, longitude } = event.target.position.coords;

console.log("Location retrieved:", latitude, longitude);

} else if (event.target.error) {

console.error("Error:", event.target.error.message);

}

}

Key attributes and properties

autolocate: Automatically attempt to retrieve location when the element loads, but only if the current permission status already allows it (preventing unexpected prompts).accuracymode: Accepts a value of"precise"or"approximate", corresponding to the standardenableHighAccuracyoption.watch: Switches behavior to matchwatchPosition(), firing events continuously as the user moves.position: A read-only property on the DOM element returning theGeolocationPositionobject once available.error: A read-only property returning aGeolocationPositionErrorif the request fails.

Styling constraints

To ensure user trust and prevent deceptive design patterns, the <geolocation>

element applies specific styling restrictions similar to the earlier

<permission> element experiment. While you can customize the button to match

their site's theme, the browser enforces several guardrails:

- Legibility: Text and background colors are checked for sufficient contrast (typically a ratio of at least 3:1) to ensure the permission request is always readable. Additionally, the alpha channel (opacity) must be set to 1 to prevent the element from being deceptively transparent.

- Sizing and spacing: The element enforces minimum and maximum bounds for width, height, and font size. Negative margins or outline offsets are disabled to prevent the element from being visually obscured or overlapping other content deceptively.

- Visual integrity: Distorting effects are limited—for example, transform supports only 2D translations and proportional scaling.

- CSS pseudo-classes: The element supports state-based styling, such as :granted (when permission is active).

Progressive enhancement strategy

We understand that standardizing new HTML elements is a gradual process.

However, developers can adopt the <geolocation> element today without breaking

compatibility for users on other browsers.

The element is designed to degrade gracefully. Browsers that don't support the

<geolocation> element will treat it as an

HTMLUnknownElement.

Importantly, if the browser supports the element, it won't render the children.

This allows writing the HTML cleanly for both supported and unsupported

browsers.

Custom fallback pattern

If you want to fully control the fallback experience yourself, you can make use of child elements like a button that you hook up with the regular JavaScript Geolocation API.

<geolocation onlocation="updateMap()">

<!-- Fallback contents if the element is not supported -->

<button onclick="navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(updateMap)">

Use my location

</button>

</geolocation>

Demo

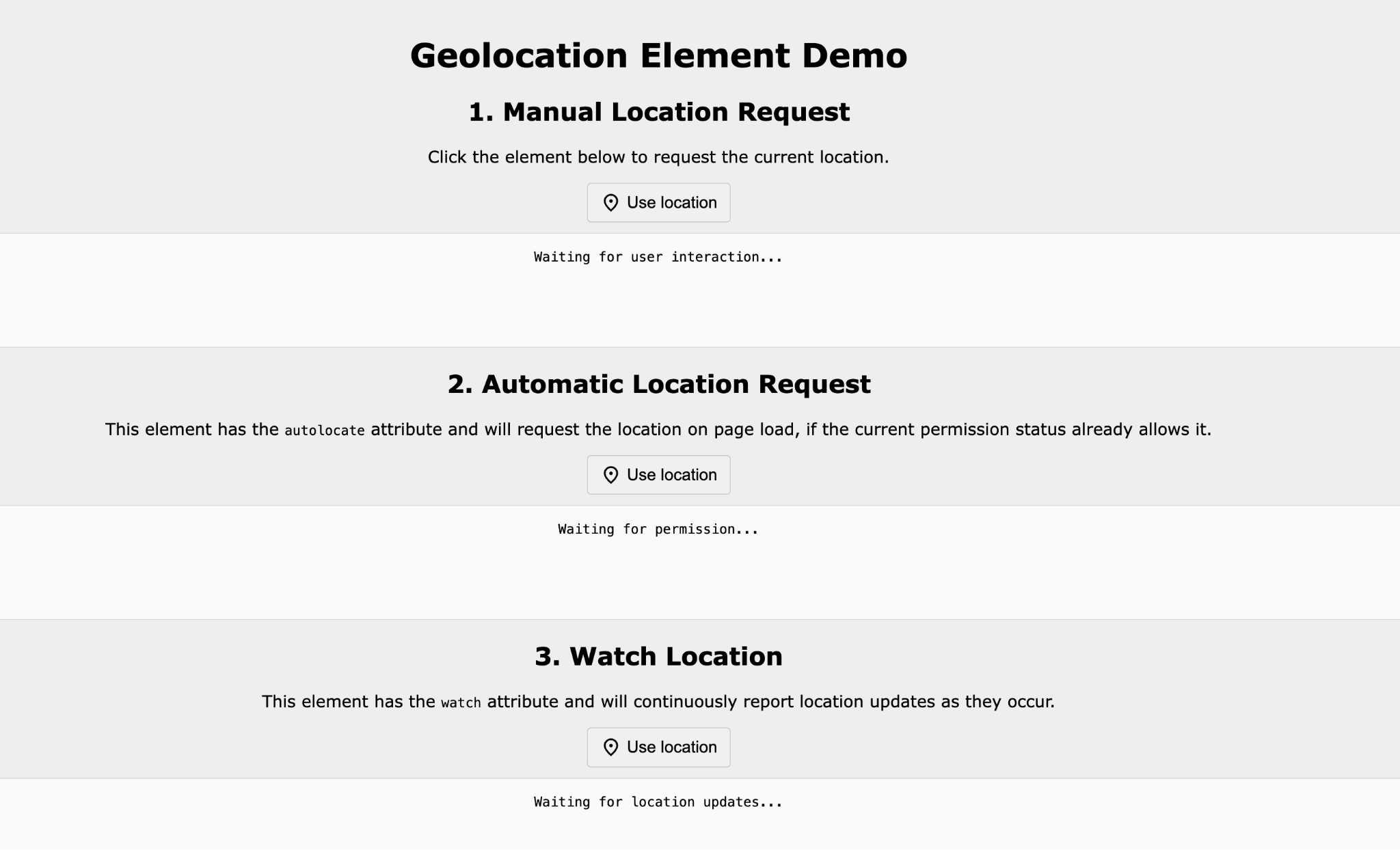

<geolocation> element demo showing the three main configurations: Manual Request, Automatic Request (using autolocate), and Watch Location (using watch). You can test these behaviors on the live demo page.Polyfill

You can alternatively install a polyfill from

npm that

transparently and automatically replaces all occurrences of <geolocation> with

a custom element <geo-location> (note the dash) backed by the regular

JavaScript Geolocation API. If the browser supports the <geolocation> element,

the polyfill simply does nothing. Check out this

polyfill demo that shows the

polyfill in action. The source

code is on

GitHub.

if (!('HTMLGeolocationElement' in window)) {

await import('https://unpkg.com/geolocation-element-polyfill/index.js');

}

<geolocation onlocation="updateMap()"></geolocation>

Feature detection

For more complex logic, you can programmatically detect support using the interface:

if ('HTMLGeolocationElement' in window) {

// Use modern <geolocation> element logic

} else {

// Fallback to legacy navigator.geolocation API

}

Wrap up

We're excited to see how developers will implement more performant location

retrial scenarios by using the new <geolocation> HTML element. It represents a

shift toward capability-specific elements that are tailored to how users

actually use the web today.

For other permission use cases, from Chrome 144 you can join the <usermedia> HTML element origin

trial, bringing these same ergonomic benefits to camera and microphone.

Related links

- The

<geolocation>element on Chrome Platform Status - Geolocation HTML Element Explainer

- Demo page

- Mozilla Standards Position

- WebKit Standards Position

Acknowledgements

This document was reviewed by Andy Paicu, Gilberto Cocchi, and Rachel Andrew.