Service workers offer incredible utility, but can be tricky to work with at first. Workbox makes service workers easier to use. However, because service workers solve hard problems, any abstraction of that technology will also be tricky without understanding it. Thus, these first few bits of documentation will cover that underlying technology before getting into Workbox specifics.

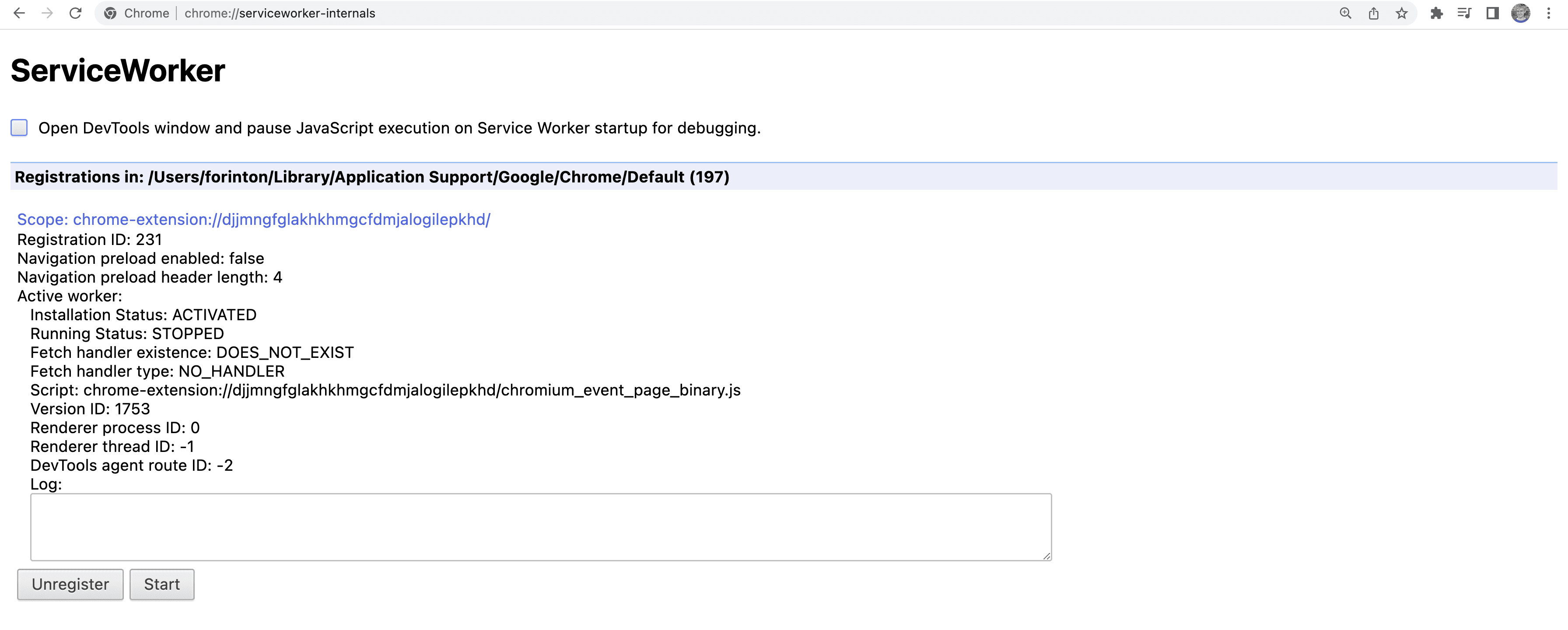

To view a running list of service workers, enter chrome://serviceworker-internals/ into your address bar.

What do service workers provide?

Service workers are specialized JavaScript assets that act as proxies between web browsers and web servers. They aim to improve reliability by providing offline access, as well as boost page performance.

A progressively enhancing, app-like lifecycle

Service workers are an enhancement to existing websites. This means that if users on browsers that don't support service workers visit websites that use them, no baseline functionality is broken. That's what the web is all about.

Service workers progressively enhance websites through a lifecycle similar to platform-specific applications. Think of what happens when a native app is installed from an app store:

- A request is made to download the application.

- The app downloads and installs.

- The app is ready to use and can be launched.

- The app updates for new releases.

The service worker lifecycle is similar, but with a progressive enhancement approach. On the very first visit to a web page that installs a new service worker, the initial visit to a page provides its baseline functionality while the service worker downloads. After a service worker is installed and activated, it controls the page to offer improved reliability and speed.

Access to a JavaScript-driven caching API

An indispensable aspect of service worker technology is the Cache interface,

which is a caching mechanism wholly separate from the HTTP cache.

The Cache interface can be accessed within the service worker scope and within the scope of the main thread.

This opens up tons of possibilities for user-driven interactions with a Cache instance.

Whereas the HTTP cache is influenced through caching directives specified in HTTP headers,

the Cache interface is programmable through Javascript.

This means that caching responses for network requests can be based on whatever logic is best for a given website.

For example:

- Store static assets in the cache on the first request for them, and only serve them from the cache for every subsequent request.

- Store page markup in the cache, but only serve markup from the cache in offline scenarios.

- Serve stale responses for certain assets from the cache, but update it from the network in the background.

- Stream partial content from the network and assemble it with an app shell from the cache to improve perceptual performance.

Each one of these is an example of a caching strategy. Caching strategies make offline experiences possible, and can deliver better performance by side-stepping high-latency revalidation checks the HTTP cache kicks off. Before diving into Workbox, there will be a review of a few caching strategies and code that makes them work.

An asynchronous and event-driven API

Transferring data over the network is inherently asynchronous. It takes time to request an asset, for a server to respond to that request, and for the response to be downloaded. The time involved is varied and indeterminate. Service workers accommodate this asynchronicity through an event-driven API, using callbacks for events such as:

- When a service worker is installing.

- When a service worker is activating.

- When a service worker detects a network request.

Events can be registered using a familiar

addEventListener API.

All of these events can potentially interact with the Cache interface.

Particularly, the ability to run callbacks when network requests are dispatched is vital in providing that sought-after reliability and speed.

Doing asynchronous work in JavaScript involves using

promises.

Because promises also underpin

async and await,

those JavaScript features can also be used to simplify service worker (and Workbox!) code for a better developer experience.

Precaching and runtime caching

The interaction between a service worker and a Cache instance involves two distinct caching concepts:

precaching and runtime caching.

Each of these is central to the benefits a service worker can provide.

Precaching is the process of caching assets ahead of time,

typically during a service worker's installation.

With precaching, key static assets and materials needed for offline access can be downloaded and stored in a Cache instance.

This kind of caching also improves page speed to subsequent pages that require the precached assets.

Runtime caching is when a caching strategy is applied to assets as they are requested from the network during runtime. This kind of caching is useful because it guarantees offline access to pages and assets the user has already visited.

When combined, these approaches to using the Cache interface in a service worker provide a tremendous benefit to the user experience,

and provide app-like behaviors to otherwise ordinary web pages.

Isolation from the main thread

The state of JavaScript performance is an evolving challenge for the web, and from a user perspective, it depends on device capabilities and access to high-speed internet. The more JavaScript used, the more challenging it becomes to build fast websites that deliver delightful user experiences.

Service workers are like web workers in that all the work they do occurs on their own threads. This means service workers tasks won't compete for attention with other tasks on the main thread. Service workers are user-first by design!

The road ahead

This documentation is just an overview. There are a few more subjects to touch on about service workers before covering Workbox proper, but rest assured: with a solid understanding of service workers, using Workbox will be an easier and more productive experience.